Over the long weekend, and in an effort to get myself back to work on my book, Reclaiming the Discarded Image, I started re-reading C.S. Lewis’s An Experiment in Criticism. In the opening chapter, he makes a distinction between the literary and the unliterary man. What is this distinction, you ask? Whether one re-reads books or not.

“The sure mark,” Lewis writes, “of an unliterary man us that he considers ‘I’ve read it already” to be a conclusive argument against reading a work.”1 He goes on to recount an example I’m sure we’ve all experienced whether externally or internally. A person, whether ourselves or an acquaintance, stands in the library or the bookstore, thumbing through a book, skimming it to see whether they’ve already read it or not. When they discover they have the book is cast aside, no longer fit for consideration because it has already been read. Of course, for the list makers among us, websites like Fable or Goodreads (I’m old enough to remember Shelfari) and the modern rise in book journals, remembering whether we’ve read a book or not may not require skimming back through its contents, but it is still often a signal that it is not to be read again. I’ve even heard the occasional “Booktuber” express the shame they feel when re-reading a favorite book when there are “so many new books to read.” Lewis could not have expected the rise of reading as a game, where one reads for number and newness, but he would still have characterized such readers as unliterary.

This isn’t because reading new books is bad. Lewis himself read many new books, but he also delighted in re-reading books. The difference for Lewis was the place the book holds for the reader. “It is pretty clear,” he argues, “that the majority, if they spoke without passion and were fully articulate, would not accuse us [literary people] of liking the wrong books, but of making such a fuss about any books at all.”2 I think this is less the case for some today. Being a reader is certainly part, often the central part, of their identity, but with many, or so I have noticed, it is still bound up with this new notion of being well-read. This no longer means having read The Odyssey or The Aeneid or The Divine Comedy or Paradise Lost. It means having read whatever is newest, what is the latest thing. And this concerns me.

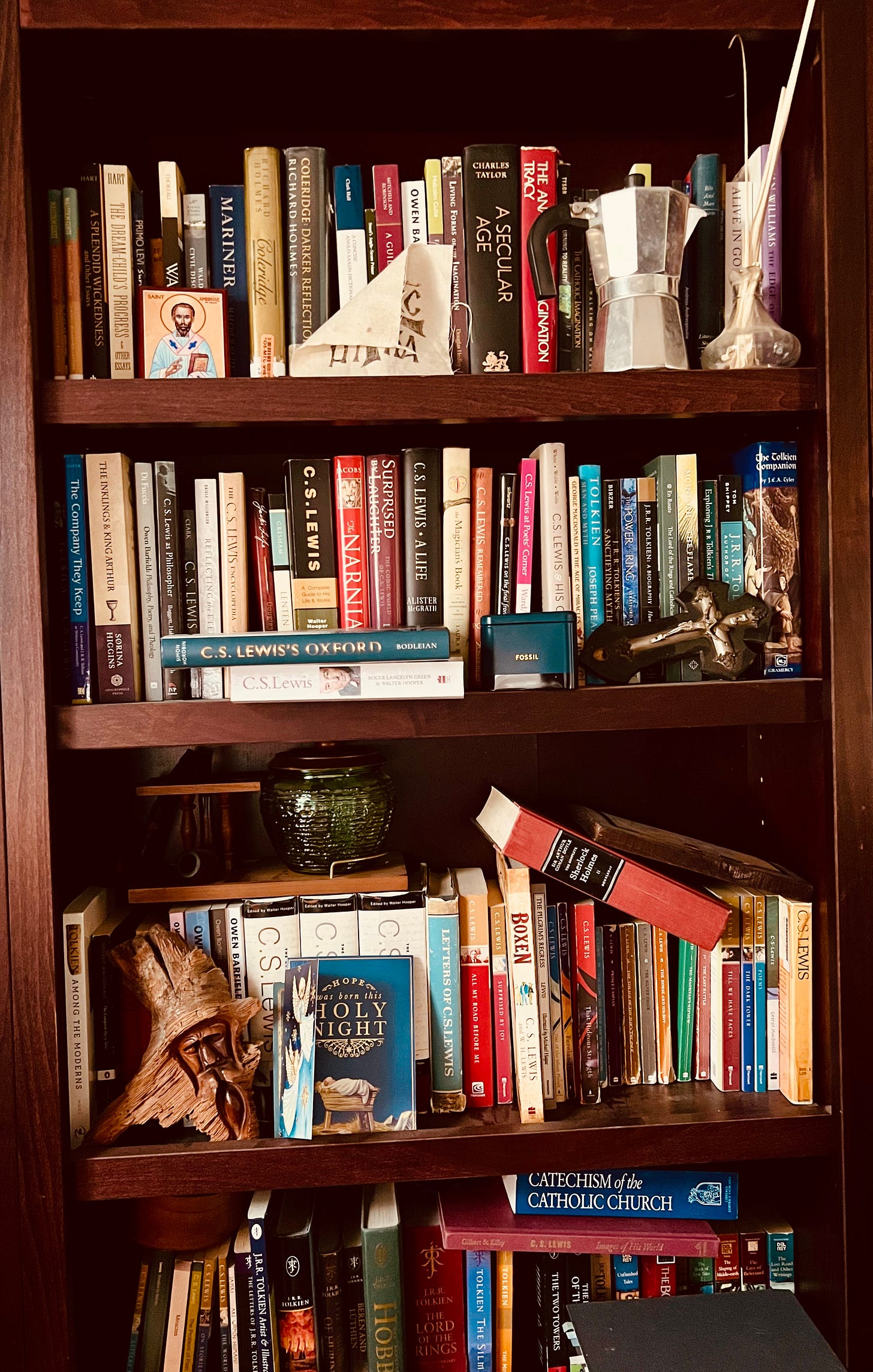

At the beginning of the chapter, as Lewis begins to characterize this difference in readers, he writes about how a taste for good books began developing in those he would consider literary at school. While others were developing a taste, if not exactly for bad books, at least for books that they intend to cast aside as soon as they are done. I was fortunate as a child. While on my own I was choosing to read Animorphs and Star Wars novels, my mother insisted I read other books as well. In this way, I fell in love with Narnia and Middle-earth, with stories of Greek mythology, Arthuriana, and later the works of Dickens and Jane Austen and the poem Beowulf. I could not count how many books I read simply to cast them aside when I was done. But I have deep memories of reading these other books, in large part because I read them still.

So what am I suggesting? That we stop reading pulp fiction? By no means. I have read and enjoyed many pulpy books. Then should we stop reading new books? Again, absolutely not! All the old books I love were once the new books of their age. And while certain arguments could be made that new books were made differently in ages past, there’s still nothing against a book simply because it is new. What I do say is this: After you have read a book, ask yourself this question, would I want to read this again? If the answer is no, and it very well could be for a number of reasons, consider making your next book one you’ve read before. In a different essay, one now easily found at the beginning of SVS’s edition of On the Incarnation by Athanasius, Lewis recommends reading one old book for every new book you read. If that is not possible, then he recommends one old book for every three new ones. I would suggest something similar. For every three books you have read for the first time, re-visit an old friend. Make the effort to enter back into the world of a book you have already read. If you don’t enjoy the experience on the second reading, then it probably wasn’t actually very good the first time around. If you find you love it just as much, if not more, then you may have found a book that will last.

I know this all sounds rather elitist. I am not against popular books because they are popular. The Lord of the Rings remains one of the most popular books of all time and I love it still and re-read it about once a year. And there may be books, whether new or old, that I have not the taste for that would do me good if I could learn to read them. So do not think I believe myself to be the gatekeeper to a world of books meant only for some and not for others. Rather, what I want to emphasize is this: Reading can be one of the most transformative things we do. In yet another essay, Lewis argues that there tend to be two kinds of readers amongst those who love reading. One reads like an Englishman on holiday who “carries his Englishry abroad with him and brings it home unchanged.”3 He goes looking for things that look like home when he reads. The other, however, is like the traveller who immerses himself in the cultures in which he travels. He drinks local wines and eats local food and comes “home modified, thinking and feeling as [he] did not think and feel before.”4 But this applies not simply to new books but to old ones as well. So let us be readers of that kind. Let us be changed by the worlds and cultures in which we walk when we read. Let us be like Bilbo who goes on an adventure, attempting to remain who he was, but coming home changed, changed, as we learn in The Lord of the Rings, into a poet himself. So re-read good books, walk in those worlds once again, and be transformed.

1 Lewis, An Experiment in Criticism, 2.

2 Lewis, An Experiment in Criticism, 3.

3 Lewis, “De Audiendis Poetis,” 2.

4 Lewis, “De Audiendis Poetis,” 3.

Another fine essay, sir. Everything you wrote in this piece is in-line with my own reading sensibilities. I stopped using goodreads precisely because I found its yearly reading challenges were discouraging me from re-reading books because I felt they somehow "wouldn't count" towards my goal of reading X-amount of books in a year

I could not agree more. I used to think that re-reading meant that I was only taking time away to read all the books I have NOT read (which is SO many; I get overwhelmed and panicky and grief-stricken just thinking about it 😩) but I have finally come to realize that no matter what I read or how fast I read I WILL run out of time to read all I want—and that’s probably a good thing because it only shows how much I want to learn.

Also, I believe re-reading a beloved book, or even just something that really made an impression on you—good or bad—is important to do because when you do you are (hopefully, ideally), not the same person you were when you read it the first time. You grow along with what you read and with what you experience first-hand in life, so there is essentially always something “new”—or just a deeper depth—to glean from revisiting a meaningful work.