As you may know, I am a teacher at a Catholic, classical high school. There are many things this means to me, and I could write whole posts on that. But today I want to share with you one of my practices as a Catholic, classical educator. In addition to reading the texts I teach (shocking, I’m sure), I try always to read something about education. Lately, I’ve been on the lookout for a good book on grammar (not to give to students, but to read for myself and to bone up on my grammar skills as well as learn the history of grammar both as a modern subject and as one of the three disciplines of the trivium). Sadly, my budget for buying such books isn’t in existence so I’m sticking to books I’ve got on hand or can get easily through the library. Recently, for instance, I started, though ran out of time to finish, Norms and Nobility by David Hicks, and just a few days ago finished The 12 Virtues of a Good Teacher by Br. Luke M. Grande, F.S.C. Currently, however, I’m re-reading a book that I think might be of broader interest: C.S. Lewis’s series of lectures published as The Abolition of Man.

This book began life as a series of lectures, 3 lectures to be precise, delivered as part of the Riddell Memorial Lecture Series at King’s College Newcastle in 1943. The three lectures were titled, “Men without Chests,” “The Way,” and “The Abolition of Man.” As I re-read this book, I want to share some of the insights I’ve gained along the way. Lewis, as always, has a wonderful ability to take a topic like education, and show us how that topic touches so many others.

In the first chapter (chapters and lectures correspond to one another and I’ll be referring to them as chapters here on out), “Men without Chests,” Lewis introduces us to problem in a prominent grammar book of his own day. He calls the book, The Green Book and its authors Gaius and Titius. He does this, not because he is afraid of reprisal, most everyone would have known what book he meant, but out of an act of respect for the authors. He does not want them to become embroiled in his criticisms, mere their ideas. If you want to know who they actually were, it’s quite easy to find out.

The main issue in this chapter begins when Gaius and Titius attempt to describe what happens when language is allowed a little too much free reign. They give as an example a time when the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was sitting looking at a waterfall when two tourists showed up. One described the waterfall as sublime, the other as pretty. For Gaius and Titius this whole scene (and Coleridge’s approval of the former understanding) highlights a problem in modern language. According to them, the tourist who describes the waterfall as sublime is merely saying he has sublime feelings about the waterfall. That is not all, however. Lewis quotes them as saying, “‘This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.’” The point for Lewis is that Gaius and Titius do not recognize that we can be right or wrong about our emotional assessments of reality.

For Lewis, this problem centers on ther recognition or rejection of what he calls the Tao. This stands in for a kind of natural law, an understanding that there can be objective things said about reality. The problem is that society has, by and large, rejected the Tao. Whether or waterfall can arouse sublime feelings in me is certainly a question we can ask. But according to Lewis’ understanding of reality, that feeling cannot be either right or wrong. One can, perhaps, hear in this notions of “my truth” vs. “your truth.” The reality of the thing or the rightness or wrongness of an emotional reaction matters far less than whether or not a person has such a reaction. And even if they do, says Gaius and Titius, that may be interesting but it is not important.

The people produced by this way of thinking, where an emotional response is purely subjective and thus not of real importance, are what Lewis calls Men without Chests. He uses the chest imagery because in the ancient and medieval worlds, the chest was seen as the seat of the spirited or passionate part of a man. The head, representing reason, rules the belly, representing the appetites, via a rightly ordered chest, representing our passions or emotions. Without chests, we become emotionless, and are left to the rule of either our heads or our stomachs. As Chesterton once quipped concerning reason ruling alone, "Poets don't go mad, but chess-players do."1

I do not know if this problem Lewis saw in his own day is quite as present now. Reason, unbalanced, has certainly been given free reign, but we do see emotion and passion coming back into play. If I am offended, my emotional reaction really matters. I may even be able to hold another person to account depending on the manner in which they offend me and the subject matter of their offense. And yet, I think all we’ve done is to say that emotional responses matter, but we have not said that they respond to reality as it really is, because there is no reality as it really is, there are only our responses. All meaning is created in the moment. So perhaps we still are living in a world of men without chests.

This essay has rather gotten away from me, and I still have not gotten to how and why this matters to me as a teacher. So before I can write about Lewis’s second chapter, “The Way,” I will have to set aside some time to write about what the Tao means for education.

In the meantime, I will leave you with this. The educational problem for those without the Tao:

[I]f they are logical, must regard all sentiments as equally non-rational, as mere mists between us and the real objects. As a result, they must either decide to remove all sentiments from the pupil’s mind; or else encourage some sentiments for reasons that have nothing to do with their intrinsic ‘justness’ or ‘ordinacy’. The latter of course involves them in the questionable process of creating in others by ‘suggestion’ or incantation a mirage which their own reason has successfully dissipated.2

In other words, if your reject the Tao but cannot get those in your care to properly reject sentiment, then you must create sentiments for them to care about.

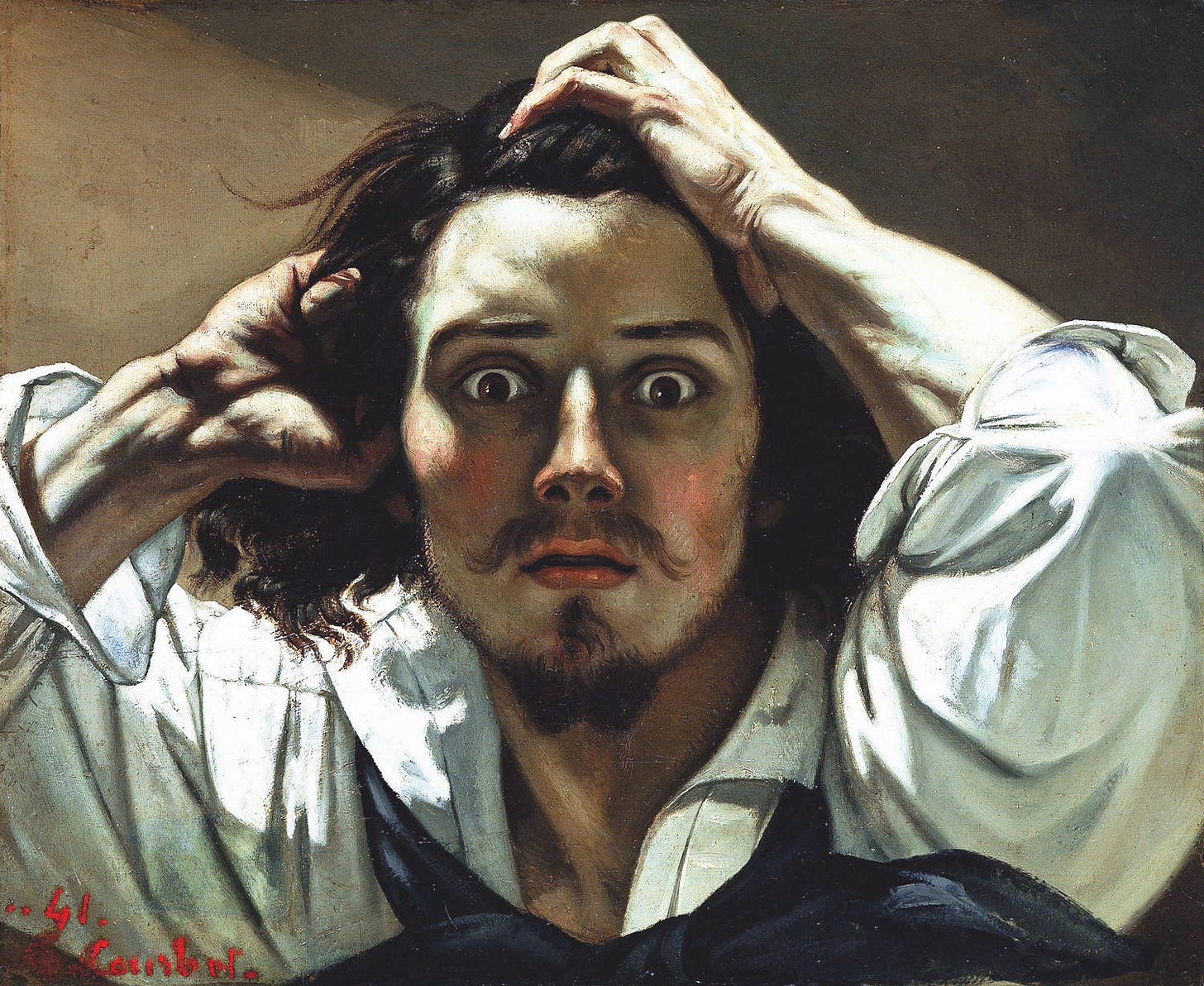

Image credit: The Desperate Man by Gustave Courbet, 1843, PD

G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (I’ve left my copy at school, but it’s in either the first or second chapter).

C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1974), 20.